On a recent trip I visited the Denver Art Museum, designed by Studio Libeskind. I first encountered the architecture of Daniel Libeskind at the Jewish Museum Berlin where the building's acute, jogging form combined with dramatic interiors and narrative-based circulation to leave a lasting impression. Libeskind's Denver Art Museum extension uses a related formal language and materiality to generate exploding shards protruding above the city street and surrounding plaza. The fractured exterior resembles a shear titanium cliff, forcing the eye up and out.

“The amazing vitality and growth of Denver — from its foundation to the present — inspires the form of the new museum. Coupled with the magnificent topography with its breathtaking views of the sky and the Rocky Mountains, the dialogue between the boldness of construction and the romanticism of the landscape creates a unique place in the world.”

Commensurate with the architecture, the exhibitions on view did not disappoint. Standouts were Mi Tierra: Contemporary Artists Explore Place and Shade: Clyfford Still/Mark Bradford.

From the museum:

“Mi Tierra: Contemporary Artists Explore Place features site-specific installations by 13 Latino artists that express experiences of contemporary life in the American West.

These artists examine diverse narratives of migration and the complex layering of cultures throughout the Western United States through ideas related to labor, nostalgia, memory, visibility, and displacement. Installations incorporate mixed media, performance-based video art, digital animation, fiber constructions, painting, sculpture, and ceramics.”

Gabriel Dawe, Plexus No. 36, 2016. Courtesy of the artist and the Denver Art Museum. © Gabriel Dawe

I've been a fan of Gabriel Dawe's work since he installed Plexus No. 25 at CAM Raleigh in 2014. In Mi Tierra Dawe's Plexus no. 36 follows a similar formula, this time incorporating a double spectrum of color, heightening the visual kinetics of the installation and increasing it's tendency for spatial distortion. As you approach, the thread gradient tricks the eye, bright colors seeming to shift and flicker as you inch closer.

“My work has to do with light, so the fourth-floor Hamilton Building ‘prow’ is a really appropriate space because in my imagination the installation is somehow coming through the long window that’s there. My installation is not only light but fragmented light, a spectrum of color. The project integrates a double spectrum, but ordered in a way that is new to my work. I had been playing with the idea of harmonic disruption, and while experimenting in the studio, I came to a solution that alternates two shifted spectrums in a single sequence. This results in a striping effect, instead of having the colors blend in a gradient—a graphic component that hasn’t been present in my work as boldly as it is here.”

Dmitri Obergfell, Federal Fashion Mart, 2016. Courtesy of the artist and the Denver Art Museum. © Dmitri Obergfell

Another standout installation, Dmitri Obergfell's Federal Fashion Mart was my first encounter with the artist's work. As I made my way through the museum, a harsh, blue fluorescent glow defied the usual careful lighting. Here, Obergfell created a rehashed Mexican market stall complete with an alter to the skeletal Santa Muerte, the popular though forbidden saint of death, chrome car bumpers, and numerous praying hands adorned with extreme stick-on nails. Installed and staged exquisitely, it transports you fully into a world of religious iconography and consumer culture.

“Obergfell believes that a community’s values are apparent if you look at its material and consumer culture. He regularly visits local markets and bodegas to survey the goods offered for sale. Using the example of Mexican markets in Denver and Mexico City, he has created a botanica, which like the commercial versions offers herbs, elixirs, figurines, and T-shirts, displayed as if for sale. In addition, the art installation brings together a pantheon of folk saints associated with the drug trade.”

On the way out I went through one final, exceptional exhibition: Shade: Clyfford Still/Mark Bradford.

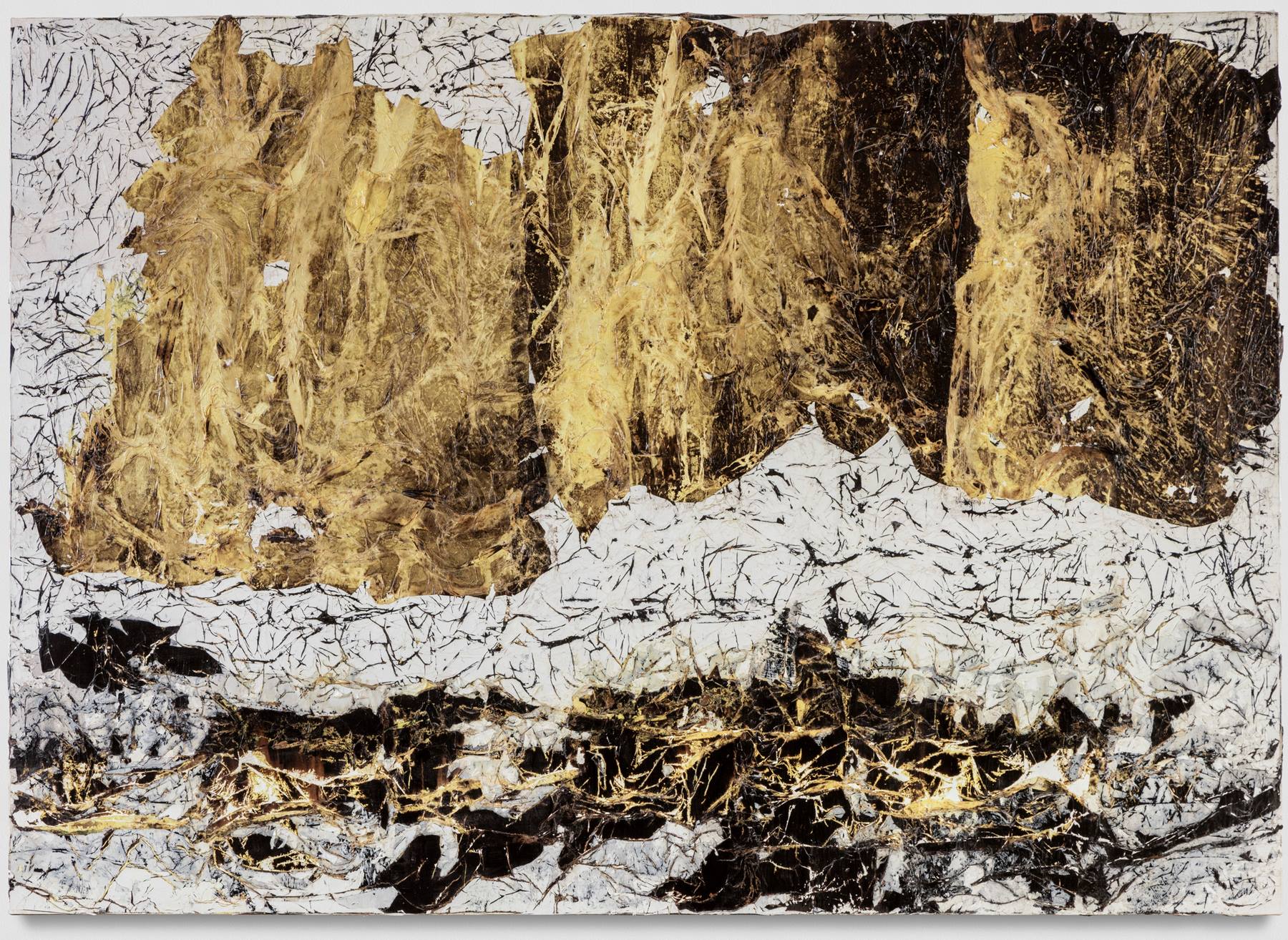

“Contemporary works and abstract expressionist masterpieces converge in Shade: Clyfford Still/Mark Bradford, a collaborative two-venue presentation by the Denver Art Museum (DAM) and Clyfford Still Museum (CSM). Paintings by renowned contemporary American artist Mark Bradford—who is representing the U.S. at the 2017 Venice Biennale—are on view at the DAM, alongside related canvases by Clyfford Still. An exhibition of Still’s work curated by Bradford is on view at CSM. Shade underscores the legacy of abstract expressionism and Bradford’s exploration of abstraction’s power to address social and political concerns.

As an African American painter, Bradford has long been fascinated by Still’s extensive use of black as a signature component of his work. Shade explores both artists’ unique relationships to black in their paintings, whether it’s used to force viewers out of their comfort zones, evoke emotions, or confront conventional notions of race.”

Mark Bradford, Butch Queen, 2016. Mixed media on canvas; 104-1/4 x 144-1/2 inches. Collection Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York, George B. and Jenny R. Mathews Fund, by exchange, 2016. ©Mark Bradford. Photograph by Joshua White.

Bradford's earth-toned works are made with collaged layers of black and white paper treated with bleach and water to bring out varying colors, then reworked with a grinder to dig into the accumulated layers of material exposing new surfaces. The resulting large-scale pieces, textured and intricate, reminded me of an active construction site peeling away layers of a city, or a seasoned bulletin board, well-worn with old news still visible below the surface.

“My practice is décollage and collage at the same time. Décollage: I take it away; collage: I immediately add it right back. It’s almost like a rhythm. I’m a builder and a demolisher. I put up so I can tear down. I’m a speculator and a developer. In archaeological terms, I excavate and I build at the same time. As a child I actually wanted to be an archaeologist, so I would dig in my backyard. When I was six, I was convinced that I could probably find a dinosaur bone there, but after about a week I realized that it was only in particular places that you find dinosaur bones. It was not like my mother stopped me. She was very good about allowing me to do, as she called them, “projects.””